Chaos Magnum Umbra Mortis

In the 1420s and 1430s, when oil and panel painting were still in their infancy, vertical formats were often used for depictions of the Last Judgement, because the narrow framing particularly suited a hierarchical presentation of heaven, earth and hell. By contrast, depictions of the Crucifixion were usually presented in a horizontal format. To fit such expansive and highly detailed representations onto two equally small and narrow wings, van Eyck was forced to make a number of innovations, redesigning many elements of the Crucifixion panel to match the vertical and condensed presentation of the Judgement narrative.

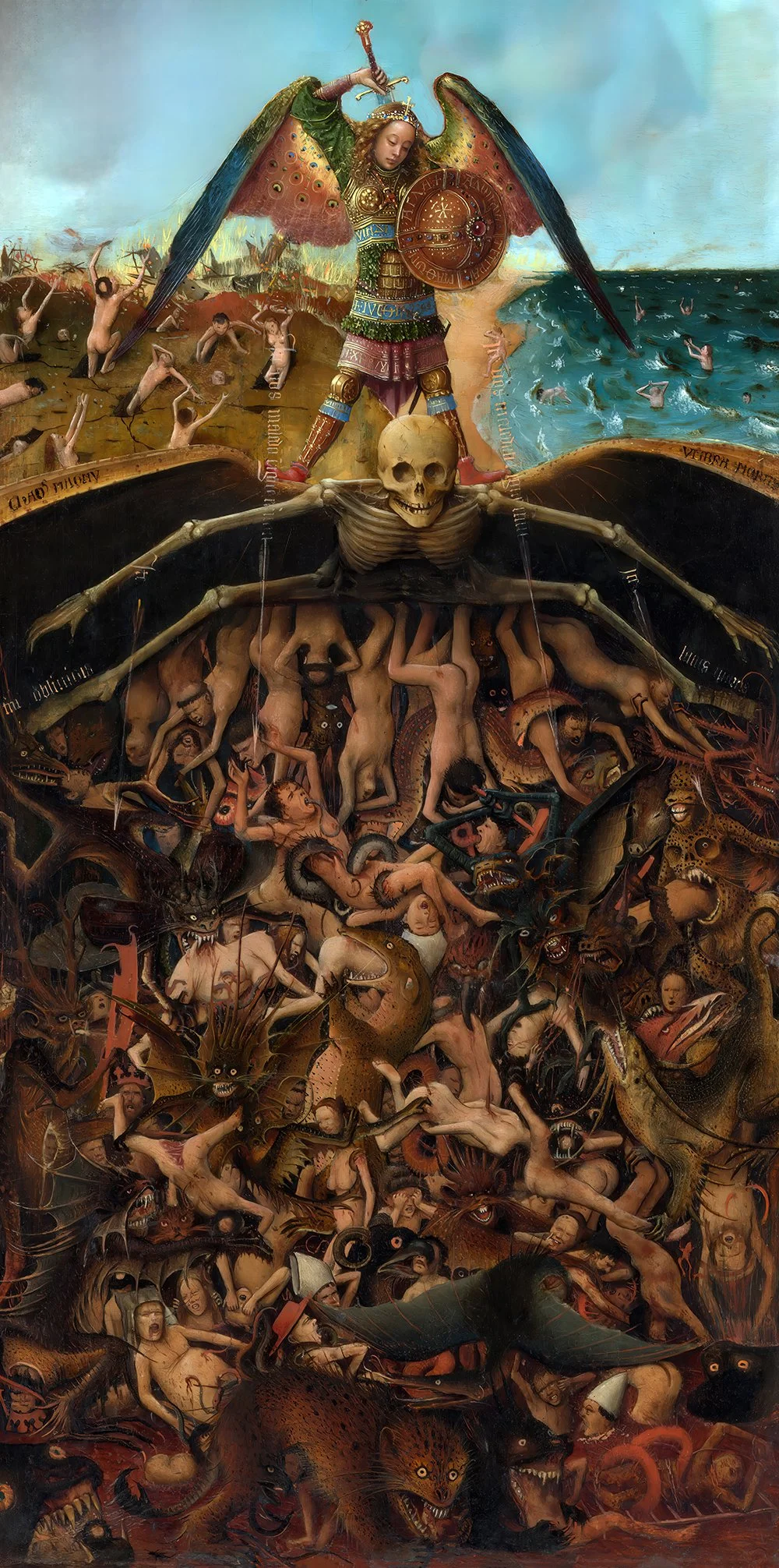

The right-hand wing, as with the Crucifixion wing, is divided horizontally into three areas. Here they represent, from top to bottom heaven, earth and hell. While Heaven is not visible in this version, earth, in the mid-ground, is dominated by the figures of Archangel Michael and a personification of Death; while in the lower ground the damned fall into hell, where they are tortured and eaten by beasts. Describing the hell passage, art historian Bryson Burroughs writes that “the diabolical inventions of Bosch and Brueghel are children’s boggy lands compared to the horrors of the hell [van Eyck] has imagined”.

The Crucifixion is not presented as a symbol of redemption, but as an act of public torture and execution, rendered with the same unsparing clarity as the damnation shown on the opposing wing. It is suffering, as much as any soul measured and cast into the depths on the other panel. There’s no abstraction or denial. The imagery which we display framed in our booth draws the eyes and sinks the hearts of the religious and non-denominational even to this day.

Paintings are typically never touched directly for restoration, particularly ones painted on wood, and for good reason: they are very easy to destroy. Age has altered the chemical composition, the moisture content, the very color in light. Even on the full Crucifixion/Judgement piece shown above as renewed by the Met, work was only done on the frame itself; the painting was never manipulated.

Technology affords us the possibility of abolishing the time, with high resolution imaging and digital manipulation, but the decisions remain:

Are those paint chips, or tiny planned daubs?

Are the lines cracks in the paint, or thin, tiny, purposeful strokes from the artist’s hands?

Is that dust and dirt? Noise from the scan? Or is it finely created cinders from Hell itself?

Intention? Or wear and time?

We can only do our best at guessing. Using our best judgment, as it were, while doing our best to honor the work without truly altering it. And it is so much work. The Judgement Panel restoration is 80 hours and counting - determination and process, and it is still unfinished. The Crucifixion, 45 hours - a panel we have never displayed. Extremely important to stay true to the art. Or else you end up with things like this:

…or unforgettable ones such as this: