From the Vaults of the Unhinged: Fortunio Liceti’s Book of Monsters

In 1616, Italian physician and philosopher Fortunio Liceti published De monstrorum caussis, natura, et differentiis libri duo (On the Causes, Nature and Differences of Monsters, in Two Books). The first edition was largely text-based, but by the time the second edition appeared in Padua in 1634 (often dated 1633)—published by Paulus Frambottus—the work had transformed into something extraordinary: a quarto volume of over 260 pages, illustrated with a gallery of the grotesque. Today, copies of this edition reside in collections such as the Wellcome Collection in London, along with other European libraries.

Liceti’s project was ambitious, even by the standards of 17th-century natural philosophy. A professor in Padua, he sought to classify and explain “monsters”—a term that encompassed everything from conjoined twins and physical deformities to fantastical hybrids of man and beast. The book sits on the strange boundary between science and folklore: part medical inquiry, part cabinet of curiosities.

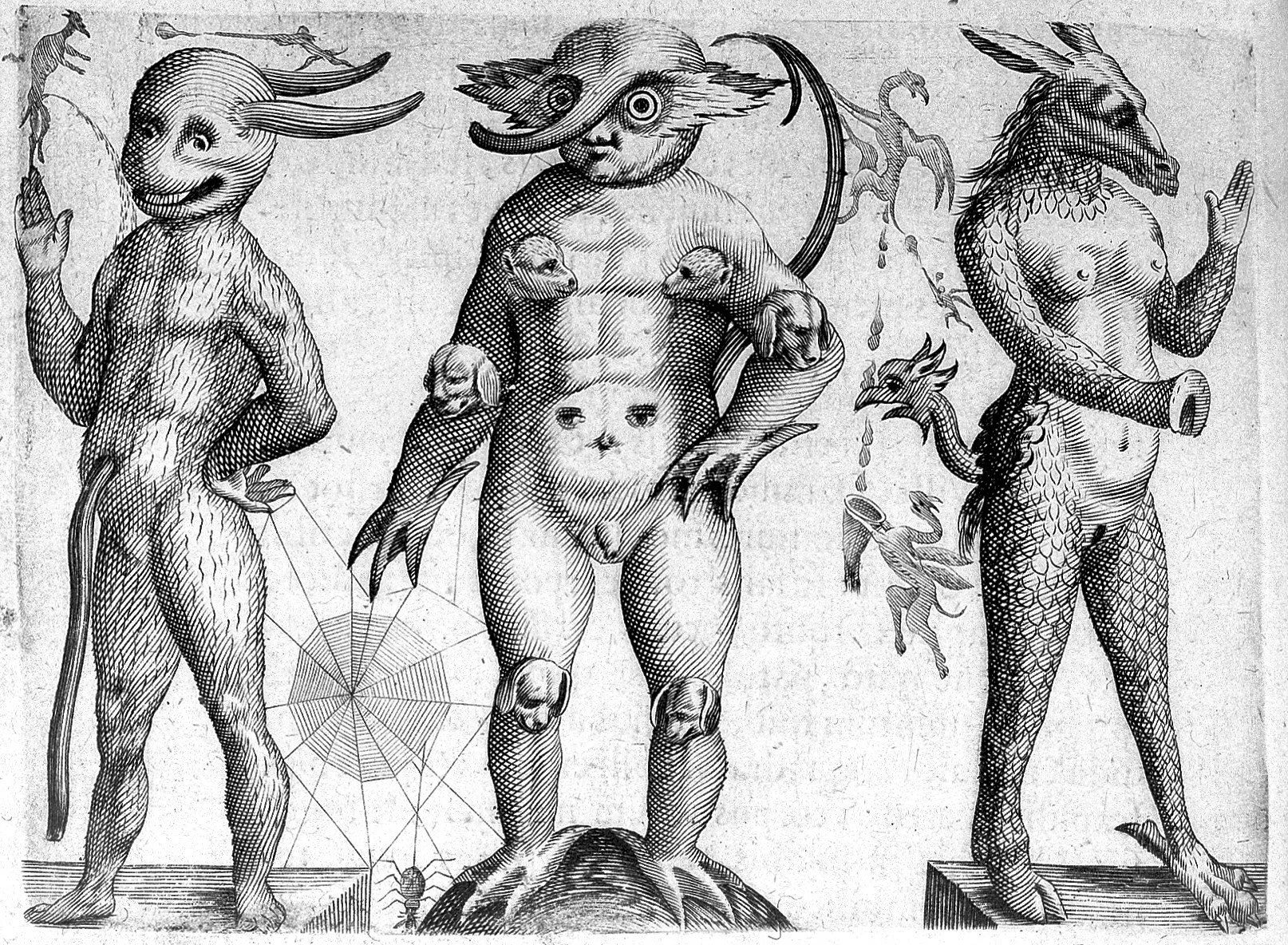

What makes Liceti’s work so compelling (and so unsettling) is the blurred line between reality and imagination. Among the woodcuts are depictions of genuine anomalies—conjoined infants, hermaphrodites, unusual birth defects—drawn with clinical precision. But alongside them appear wildly imagined beings: humans with elephant heads, animals fused together in impossible ways, horned people, and creatures lifted straight from nightmare. Liceti attempted to explain both kinds of “monsters” using the tools of his era: Aristotelian and Galenic biology, theories of reproduction involving male and “female seed,” environmental influence, even hereditary transmission. For his time, this wasn’t far removed from the beginnings of what would later become genetics.

The result is a volume that is equal parts medical curiosity and dark wonder. The engravings are executed with startling detail—sometimes bordering on reverence, other times evoking horror. They tell us as much about early modern anxieties as they do about biology: a world where the boundaries of the human body, the natural order, and divine punishment were constantly in question.

De monstrorum remains, even now, a fascinating artifact of how people once wrestled with the edges of the “normal.” To flip through its pages is to glimpse both the birth of scientific classification and the lingering pull of myth—a reminder that the line between observation and imagination has always been thinner than we’d like to think.