Resurrected Relics: Reviving Paul Pfurtscheller’s Charts

Housefly (Musca domestica) by Paul Pfurtscheller

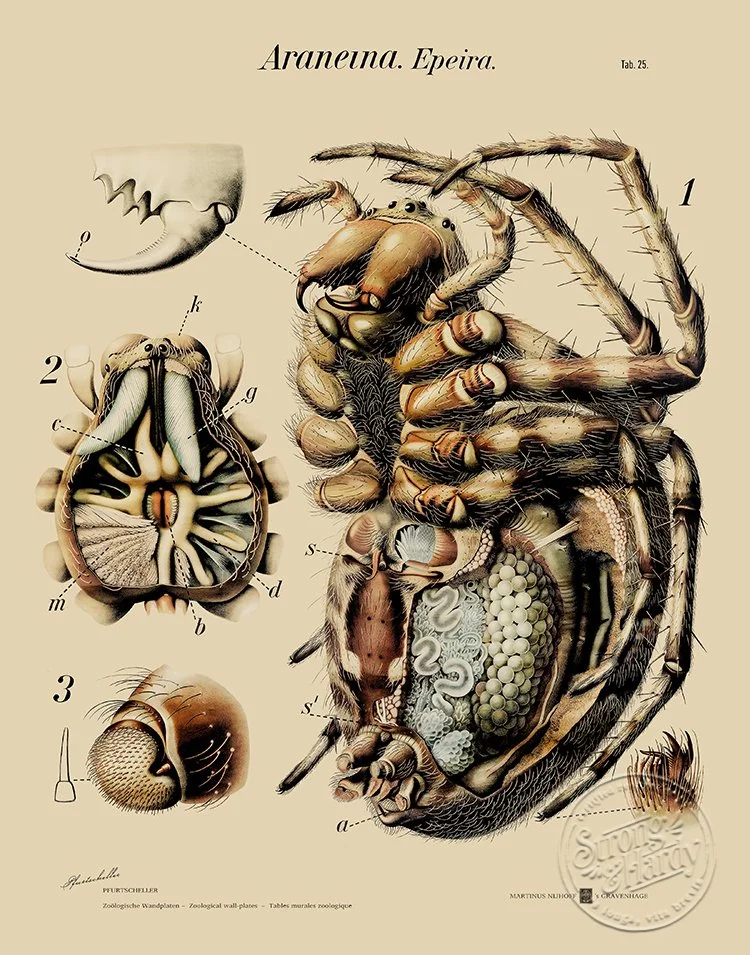

At the turn of the 20th century, Austrian zoologist and artist Paul Pfurtscheller (1855–1927) brought science to life through a series of zoological wall charts that remain some of the most striking examples of educational illustration ever created. What began in 1902 as a modest teaching tool for German-speaking classrooms quickly evolved into a worldwide standard for biological education—uniting scientific rigor with extraordinary artistic skill.

A Zoologist with an Artist’s Eye

Pfurtscheller was not just an illustrator; he was a trained zoologist and a member of the Zoological and Botanical Society of Vienna. His deep understanding of animal anatomy informed every stroke of his brush. He began his series of Zoologische Wandtafeln (Zoological Wall Charts) in 1902, publishing them through A. Pichler’s Witwe & Sohn in Vienna and Leipzig.

The charts were designed to hang in classrooms, offering students large, detailed views of animal anatomy at a time when projectors, slides, and digital screens didn’t exist. Each plate combined accuracy with a kind of quiet grandeur: spiders rendered with delicate precision, honeybees dissected into elegant layers, and snakes unfurled in bold, almost decorative compositions.

Global Reach and Enduring Influence

Although they originated in Austria, Pfurtscheller’s charts spread rapidly across Europe and beyond, gaining popularity in universities and secondary schools around the world. They were sold individually, often varnished for durability, and used extensively by zoologists—including at the University Zoological Institute in Vienna. Their clarity and quality earned them high praise among educators and scientists alike.

Earthworm (Lumbricus terrestris) by Paul Pfurtscheller

Pfurtscheller produced 38 plates of a planned 70 before his death in 1927. A 39th chart, illustrating the dissection of the Oriental cockroach (Blatta orientalis), was completed posthumously based on his notes. His work spanned invertebrates, insects, amphibians, reptiles, and more—each plate meticulously labeled and composed to balance scientific accuracy and aesthetic harmony.

Restoring a Lost Masterpiece

More than a century later, many of these wall charts survive only in faded, damaged, or poorly scanned forms. High-quality digital reproductions are surprisingly difficult to find, particularly for some of the rarer plates.

That’s where our work comes in. Over the past months, we’ve dedicated countless hours to digitally restoring these incredible works—cleaning up grainy scans, repairing tears and discoloration, and bringing back the vibrancy and precision that Pfurtscheller originally intended.

So far, we’ve resurrected six of his charts:

Garden Spider (Araneus diadematus)

Earthworm (Lumbricus terrestris)

Housefly (Musca domestica)

Mosquito (Culex pipiens)

Western Honeybee (Apis mellifera)

Grass Snake (Natrix natrix)

Each restoration is both a technical challenge and a labor of love. Our goal is to build a comprehensive digital library of Pfurtscheller’s educational masterpieces, preserving them for future generations of artists, scientists, and curiosity-seekers alike.

Why It Matters

Pfurtscheller’s charts sit at a fascinating intersection of art, science, and education. Long before “STEM” and “STEAM” became buzzwords, his work demonstrated how the visual arts could illuminate complex scientific ideas. His charts don’t just document anatomy—they elevate it, transforming scientific subjects into objects of beauty and wonder.

In a world saturated with high-resolution photographs and 3D models, Pfurtscheller’s work reminds us that illustration is not merely decorative. It’s a way of seeing—an act of interpretation that reveals structure, function, and aesthetic harmony in ways photographs often can’t.